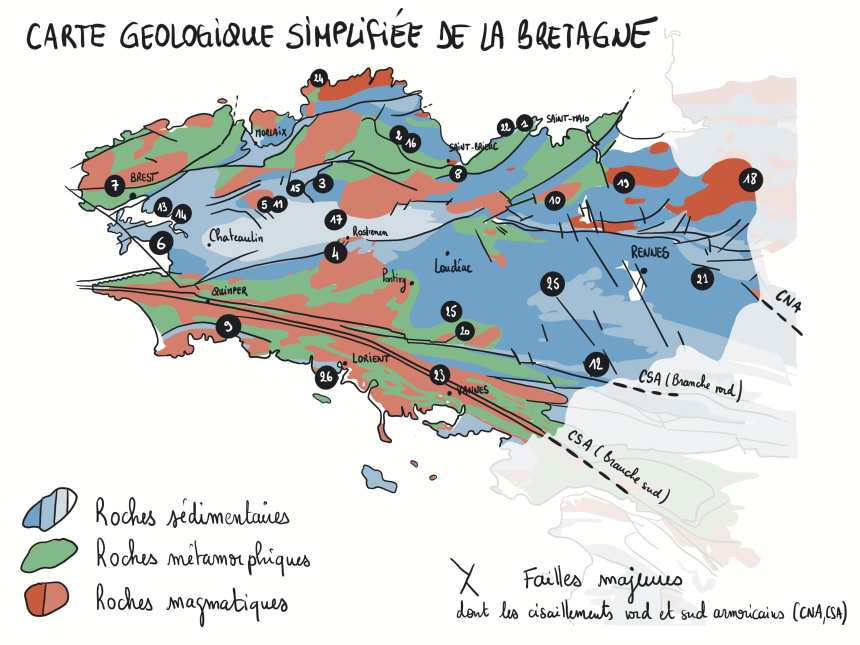

A Complex Geology

The simplified geological map of Brittany reveals the composition and structure of its subsurface. The colored areas represent geological units. The black lines, curved or straight, mark major breaks: faults. This graphic patchwork illustrates a certain complexity.

A Long... Fragmented History

Brittany belongs to the Armorican Massif. It houses the oldest rocks in France dated at about 2 billion years. These are not very numerous. The majority of Breton rocks tell a long story of 750 million years, with, it must be noted, some amnesias during the last 300 million years. Geological information is not always preserved. This long history testifies to global geological phenomena.

A Global Dynamics

The surface of our planet is a true dynamic puzzle made up of pieces of different sizes, the tectonic plates (see installation 20). Driven by the Earth’s internal kinematics, they move, join, break apart, overlap, and rub against each other. The appearance of the planet thus changes over millions of years. Continents break up, come together, oceans open and close, mountains rise and erode... But behind this apparent disorder lies a form of cyclicity: geological events repeat themselves.

Formation of Two Mountain Chains

Many Breton rocks, deformed, transformed, melted, bear witness to the formation of two mountain chains: the Cadomian chain between 650 and 540 Ma, and the Hercynian chain between 360 and 300 Ma. These two orogenies result from the convergence of tectonic plates. In other words, the present Armorican Massif results from the assembly of fragments of ancient plates. The rocks in southern Brittany once belonged to the legendary supercontinent Gondwana, before becoming part of the current Eurasian continent.

Birth and Disappearance of Oceans

Two types of rocks testify to these oceanic epics. The first are sedimentary rocks. Fossils found in these rocks, such as marine arthropods (trilobites) or fossilized sand ripples, are remarkable evidence of their marine origin. The other rocks are magmatic, such as ancient gabbros or basalts. These rocks are generally associated with existing or emerging oceanic domains. They constitute irrefutable proof of the existence of ancestral oceanic areas. In other words, a large part of Breton rocks were formed in seas or oceans that no longer exist today!

Geologists estimate that in the Paleozoic era (541 Ma - 252 Ma), for about 130 million years (from 480 Ma to 350 Ma), sediments deposited in oceanic environments accumulated to a thickness of 5 to 6 kilometers.

Volcanoes that Spout!

Volcanic edifices no longer exist. However, some geological formations consist of ancient volcanic products: lava flows or ash deposits, etc. The previously mentioned Cadomian chain was a mountain range similar to the current Andes in South America. Pillow lavas, rarer in the territory, come from episodes of submarine volcanism.

Different Climates

Quartzite pebbles found at over 140 m altitude around Mount Menez-Hom, near the Crozon Peninsula, the deposits of “red sands” (see installation 25), and the faluns are also witnesses to sea level variations driven by past climate changes. More recently, only 20,000 years ago, during the last glacial maximum, the near-surface Breton rocks were heavily fragmented by frost action. At that time, the sea level was about -125 m. Our ancestors could reach Ireland or England on foot!

A Journey in Latitude

Sedimentary rocks are good climate recorders. Breton limestones dated to 410 million years contain coral fossils. These reef organisms indicate a warm climate and shallow sea. Paleogeographic reconstructions place the (future) Armorican Massif at that time near the Tropic of Capricorn in the southern hemisphere. Both sediments and lavas record the latitudinal movements of tectonic plates.